"In the days when it was common for poor folk to eat acorns (glans in Latin), walnuts were called Jovis glans, the nuts of Jove (Jupiter), king of the gods. Later, they came to be known as Juglans regia, or royal nut, and that remains its botanical name. In Roman times they were also known as Persian nuts for they may have been introduced to the empire by way of Persia. "

"In the days when it was common for poor folk to eat acorns (glans in Latin), walnuts were called Jovis glans, the nuts of Jove (Jupiter), king of the gods. Later, they came to be known as Juglans regia, or royal nut, and that remains its botanical name. In Roman times they were also known as Persian nuts for they may have been introduced to the empire by way of Persia. "

"In classical times, when it was believed that the shape of a particular food denoted its usefulness, walnuts were considered fodder for the brain. The green husk was likened to the human scalp; the hard nut shell to the skull; the papery partitions to the membrane; and the nutmeat to the two hemispheres of the brain, explained Waverly Root in "Food" (Konecky & Konecky, 1980). "

"According to Roman lore, the gods feasted on walnuts while their lowly subjects subsisted on lesser nuts such as acorns, beechnuts, and chestnuts. Walnuts were thrown to Roman wedding guests by the groom to bring good health, to ward off disease and increase fertility. Young boys eagerly scrambled for the tossed walnuts, as the groom's gesture indicated his passage into manhood. In Rome, the walnut was thought to enhance fertility, yet in Romania, a bride would place one roasted walnut in her bodice for every year she wished to remain childless. "

"Early cultivation spanned from southeastern Europe to Asia Minor to the Himalayas. Greek usage of walnut oil dates back to the fourth century B.C., nearly a century before the Romans."

"To the ancient Greeks, walnuts were karyon basilikon or persikon -- royal or Persian walnut, noted Alan Davidson in "The Oxford Companion to Food" (Oxford University Press, 1999). But he leaves out a delightful tale related in "The Walnut Cookbook": In Greek mythology, Dionysus, the god of wine, fell in love with a maiden named Carya. When she died suddenly, he transformed her into a walnut tree. (There's that wine and walnuts connection again.) "The goddess Artemis carried the news to Carya's father and commanded that a temple be built in her memory. Its columns, sculpted in wood in the form of young women, were called caryatides, or nymphs of the walnut tree -- so the tree furnished the image for a famous Greek architectural form," wrote Toussaint."

See also: Walnuts

"An

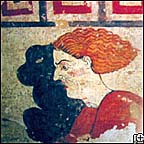

"An  "Etruscan art, made of strange demons and monsters, is emerging in a Tuscan village, in what could be one of the most important discoveries of recent times, according to scholars who have seen the paintings."

"Etruscan art, made of strange demons and monsters, is emerging in a Tuscan village, in what could be one of the most important discoveries of recent times, according to scholars who have seen the paintings."